This February Airbus announced that it would phase out production of its 380 double decker jumbo after its main customer, Emirates Airlines, decided to stop buying them. The 380 was a marvelous work of aerospace engineering that lost a lot of money for Airbus.

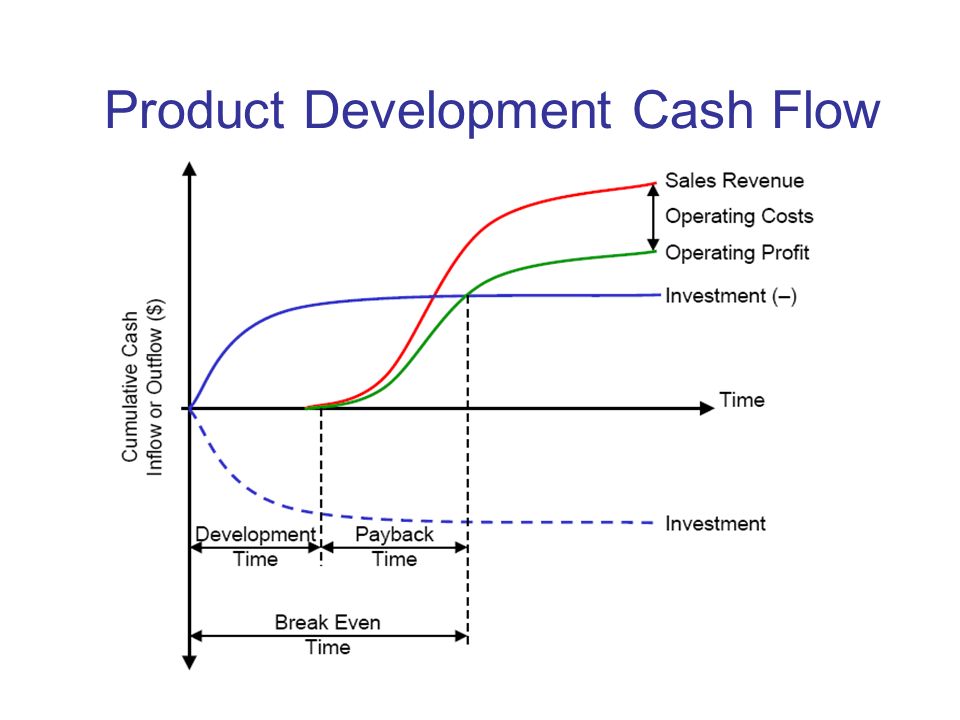

The development of the 380 roughly paralleled the development of Boeing’s 787 (2001 – 2008). It cost the company about $25 billion to develop. In a well-publicized gaffe, development was delayed by 2 years because of a misalignment of wiring in the plane caused by different development teams using different versions of CAD software.

Airbus’ total deliveries of the 380 will be around 250 planes. It would have needed to make a profit of $90 million per plane in order to break even. Unfortunately, like Boeing, Airbus was probably losing money on every plane shipped, so it will never recoup that original $25 billion investment.

Again, there were certainly spinoff benefits to Airbus, and the company remains financially strong, in part because of government support. But the opportunity cost remains huge – what else could Airbus have done with that $25 billion that would have been a more profitable investment? And that doesn’t even begin to consider the cost to airports of installing double decker jetways to load and unload the planes.

What went wrong? Airbus badly misread the civil aviation market. It decided that airlines would increasingly want to fly large numbers of people (the plane held more than 500) internationally from hub to hub. But outside of Emirates (their main customer, by far), not many did. Instead, airlines increasingly want to fly smaller, more efficient planes (the 787 has two engines to the 380’s four) from point to point. In this way, Boeing was better at reading the market.

The 380 is a wonderful plane, and many people love flying in it. But it was a bad investment.