We are in an innovation race. Global competition has never been fiercer for companies, and not only in the high technology sector. From food and agriculture, to renewable energy and automobiles, leaders are wondering: How do I accelerate innovation?

Many of them are focusing on the wrong activities. Despite changes in technology, many companies are using outdated approaches to product and service development. As a result, they are missing the real opportunities to accelerate innovation.

Manage the Right Activities

Most companies spend a lot of effort tracking product and service development projects. Once a project is approved for development, it gets tracked (and often led) by a program manager. Status is reported to management, often on a weekly basis.

New technologies and development methodologies have accelerated project execution. Software development is faster due to error-checking tools, continuous integration and deployment tools, and the widespread adoption of Agile. Hardware development, while still facing the reality of having to build physical things, has been revolutionized by the advent of 3-D printing and fast prototyping.

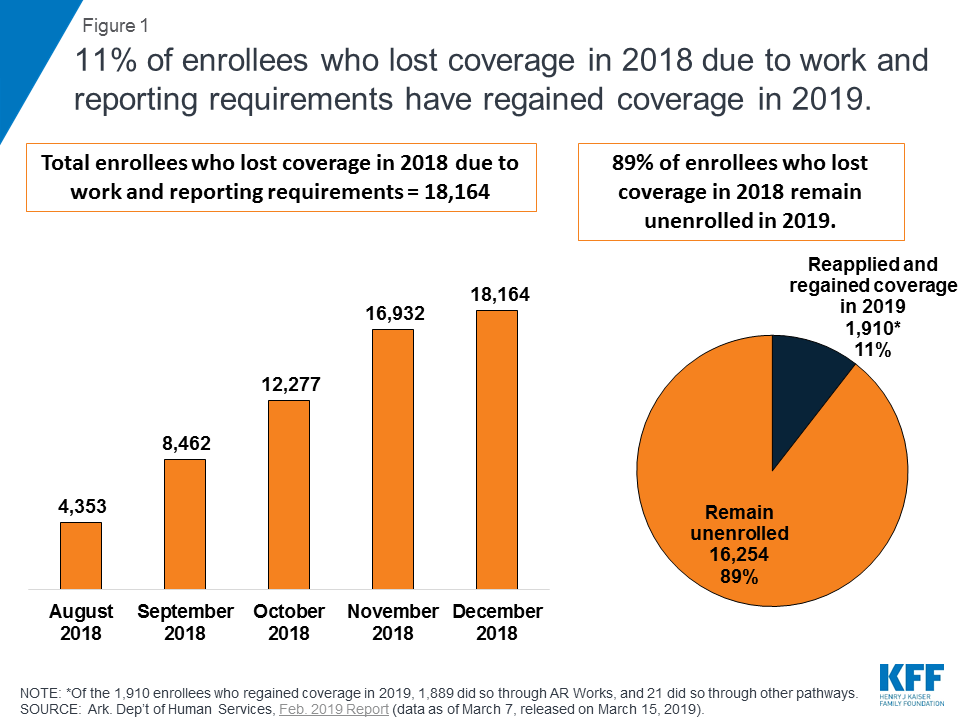

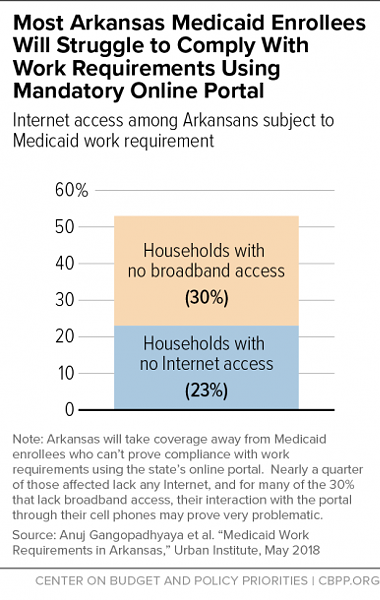

Don’t get me wrong: Projects can certainly go off the rails, encounter unexpected technical problems, and end up late – sometimes staggeringly so. (Remember the deployment of the federal health insurance marketplace portal in 2013?) But I think most companies are missing the real opportunities to accelerate innovation:

- Time to invest

- Time to define

- Time to make decisions

Let’s explore each of these in turn.

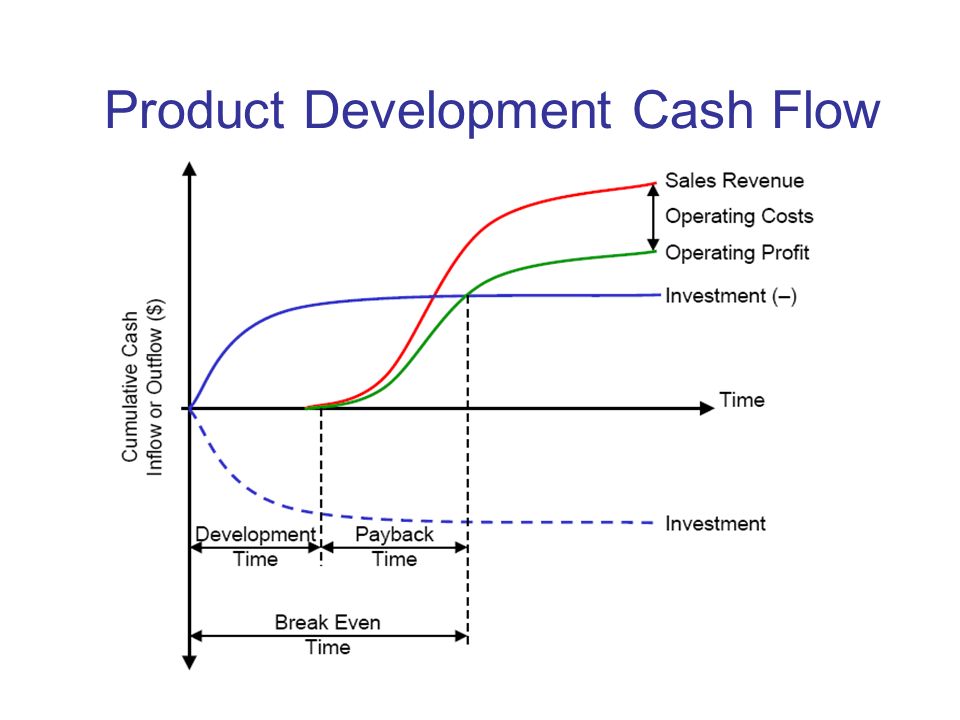

1. Time to Invest

Most products are late to market not because of delays in project execution, but rather because it took too long to start the project. Companies don’t invest the time and energy in managing the process before committing. Ideas percolate around, get discussed and fought over, but have a hard time getting funded.

In addition, the tyranny of the annual operating plan often results in product and service proposals being bundled into an end of year request for funding. As markets and competitors move ever faster, this makes less and less sense.

Does your company have a clear process for vetting and funding new ideas? Do you measure the time from idea to funding, rather than from funding to launch? What percentage of people’s time is devoted to these activities?

Some will say there is too much uncertainty about the technology or markets to make an earlier commitment. True – new product and service development is all about managing uncertainty. Are there ways to manage this? Absolutely. And I would contend that the potential benefits — of hitting the market at an earlier time — often outweigh the risks.

2. Time to Define

You have many design options with any new product or service. Product architects propose subsystems and systems. Product managers propose requirements to meet customer and other needs. Eventually these are solidified into a set of requirements (what the product or service must do) and specifications (how it does them). This activity is often accomplished through proofs of concept (POCs) which allow designs to be tested out.

You can accelerate this activity with new tools and methodologies. Simulation software can run virtual tests of new hardware and software designs, even complex ones. Online A/B testing allows for quick user feedback on possible features. Applying Agile methods to the design process, through activities such as Design Sprints, increases the sense of urgency and shortens the design time. New capabilities in artificial intelligence allow for the creation and evaluation of multiple designs in a shorter period of time.

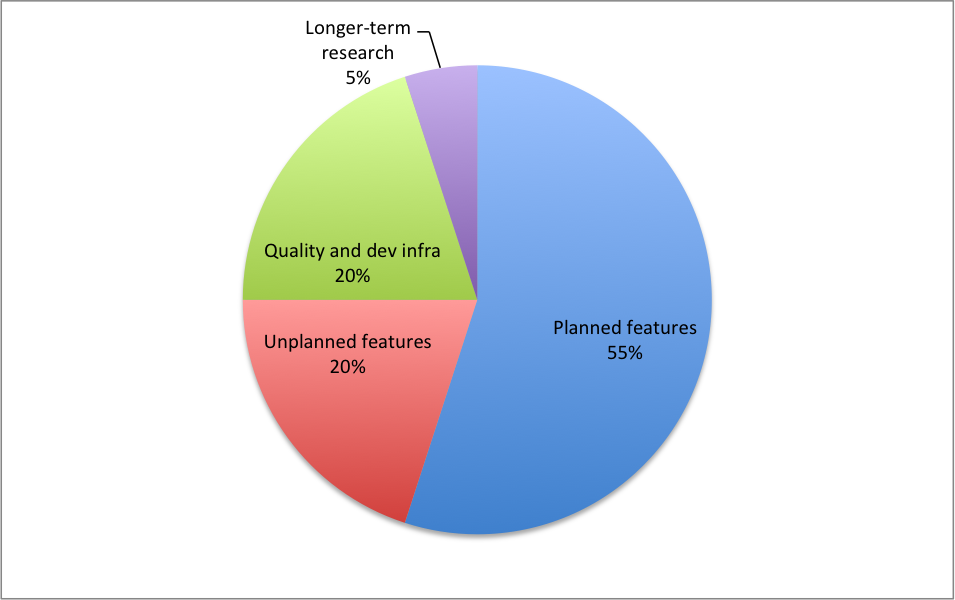

How many resources do you devote to these activities? POCs often compete for resources with existing development projects and maintenance of current products. Do you manage these tradeoffs strategically or just respond to them one-by-one? And have you assessed the benefit of investing in and using these new tools?

3. Time to Decision

Product and service development involves making hundreds of decisions, not only about product definition and technology approaches, but about resources, schedule, pricing and positioning, etc. Sometimes the decision making process seems like it takes longer than the design and development process.

Most companies are unaware of this opportunity to speed up innovation because they don’t consider it. But I have seen projects slowed down by weeks, even months, waiting for decisions to be made. Often this is because decision making responsibility is unclear — who gets to decide? And when decisions get pushed up the corporate ladder to senior executives with limited bandwidth, it can really slow things down.

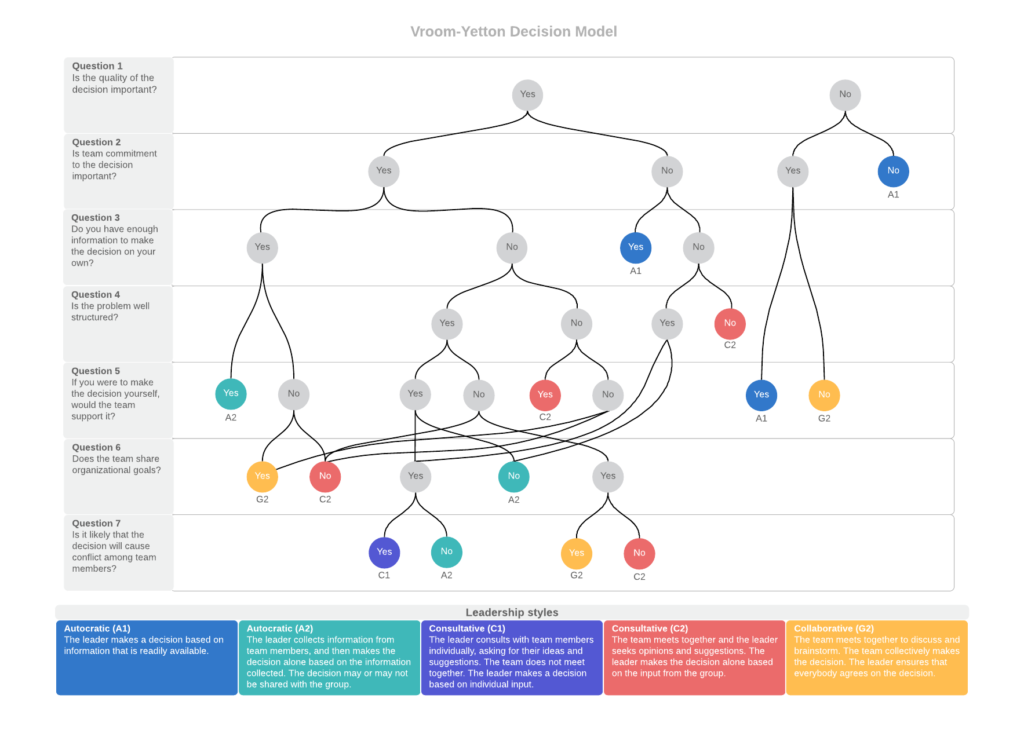

Fundamentally, decisions get pushed up the ladder because senior management doesn’t trust people in the organization to make good decisions. But how valid is this? Not all decisions are created equal. The information needed to make a good decision and the risk of making a bad decision can vary widely.

Boundary conditions are a time-tested approach allowing project leaders to know when they can make decisions themselves, and when they need to escalate. Some version of that combined with clear definition of ownership can dramatically improve decision making velocity.

As always, I appreciate your comments on these articles. Contact me if you’re interested in accelerating innovation in your organization.