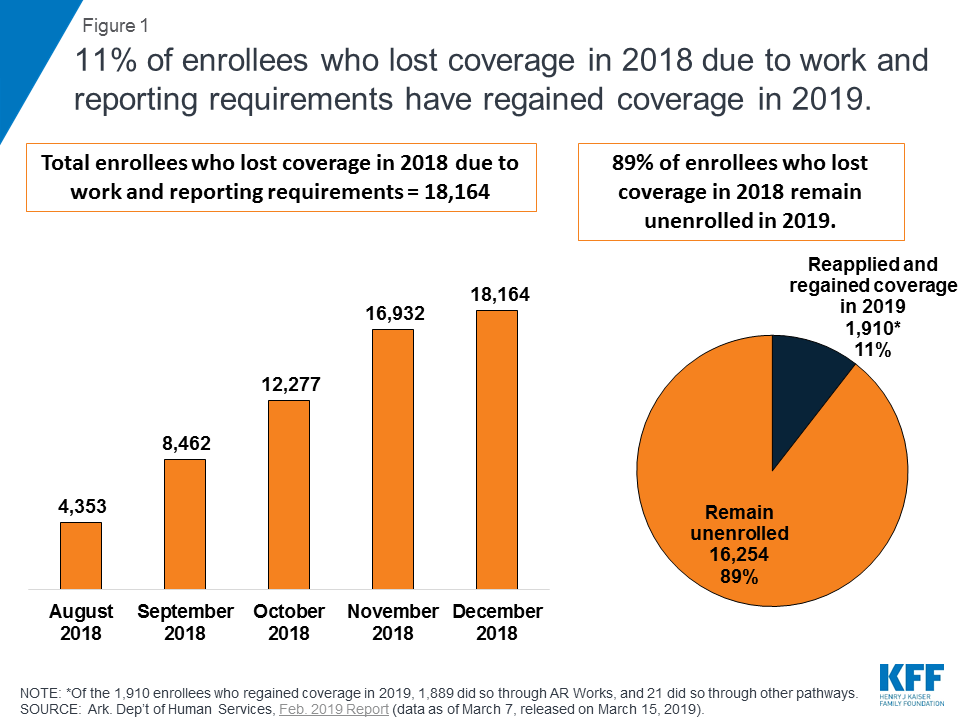

An article in the February 16th issue of The Economist talked about Arkansas’ rollout of work requirements for Medicaid recipients. It makes for depressing reading. 18,000 recipients (about 7% of the total) lost their Medicaid coverage, not because they didn’t qualify, but because the program was poorly designed to meet their needs.

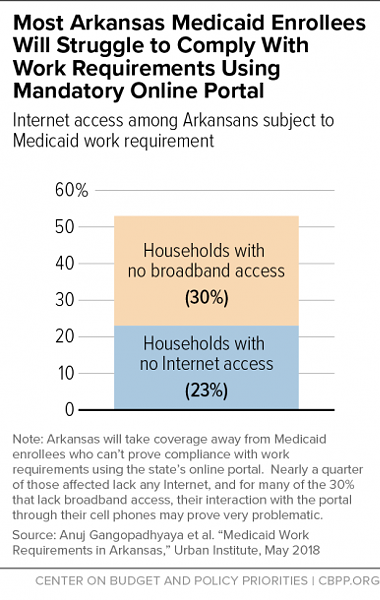

For example, recipients were required to report their work activities online. But more than 20% of recipients lack access to the internet through a computer or a smartphone. Many struggle to find public transportation to a library that has internet access. Even more astounding, the website for reporting shuts down between 9 pm and 7 am, making it largely inaccessible to working people. Letters to recipients documenting the changes in policy had little effect, either because the recipients couldn’t read English adequately, couldn’t understand the writing (have you ever gotten a letter from a public agency?), or were no longer living at the address.

Most of these people only discovered that they had been dropped from Medicaid when they went to a pharmacy to pick up a prescription and learned that the price had increased considerably.

Did anyone in the Arkansas Department of Human Services actually go talk to or observe a customer, a clinic, doctor, nurse or social worker? It seems unlikely. Anyone who has worked with Medicaid recipients knows that their housing can be insecure (they move frequently, or occasionally go homeless), lack access to public transportation, lack access to the internet (they may have phones, but can only afford limited minutes), lack literacy or language skills, and may have behavioral issues that prevent them from understanding choices. If the state had talked to stakeholders, they could have designed services that met the needs of the users. At least if they had done concept testing, they would have discovered that the proposed services were badly flawed.

There is a better way. An article in the New York Times on March 1 discussed new public housing in the Hackney borough of East London. The architecture firm that was hired by the borough worked closely with current residents (whose old public housing was to be torn down and replaced) to understand their needs. The resulting mid-rise buildings contain subsidized apartments that are light and airy with winter gardens and balconies. Subsidized and market rate apartments share entrances, floors and open spaces, so there is no stigma attached to subsidized housing.

Public services need not be poorly designed. In fact, many agencies around the country are starting to embrace user-centered design. Sure, funding can be a challenge, but that just places an additional constraint on the design process. Talking to customers and stakeholders while designing public services can improve the lives of millions of Americans.